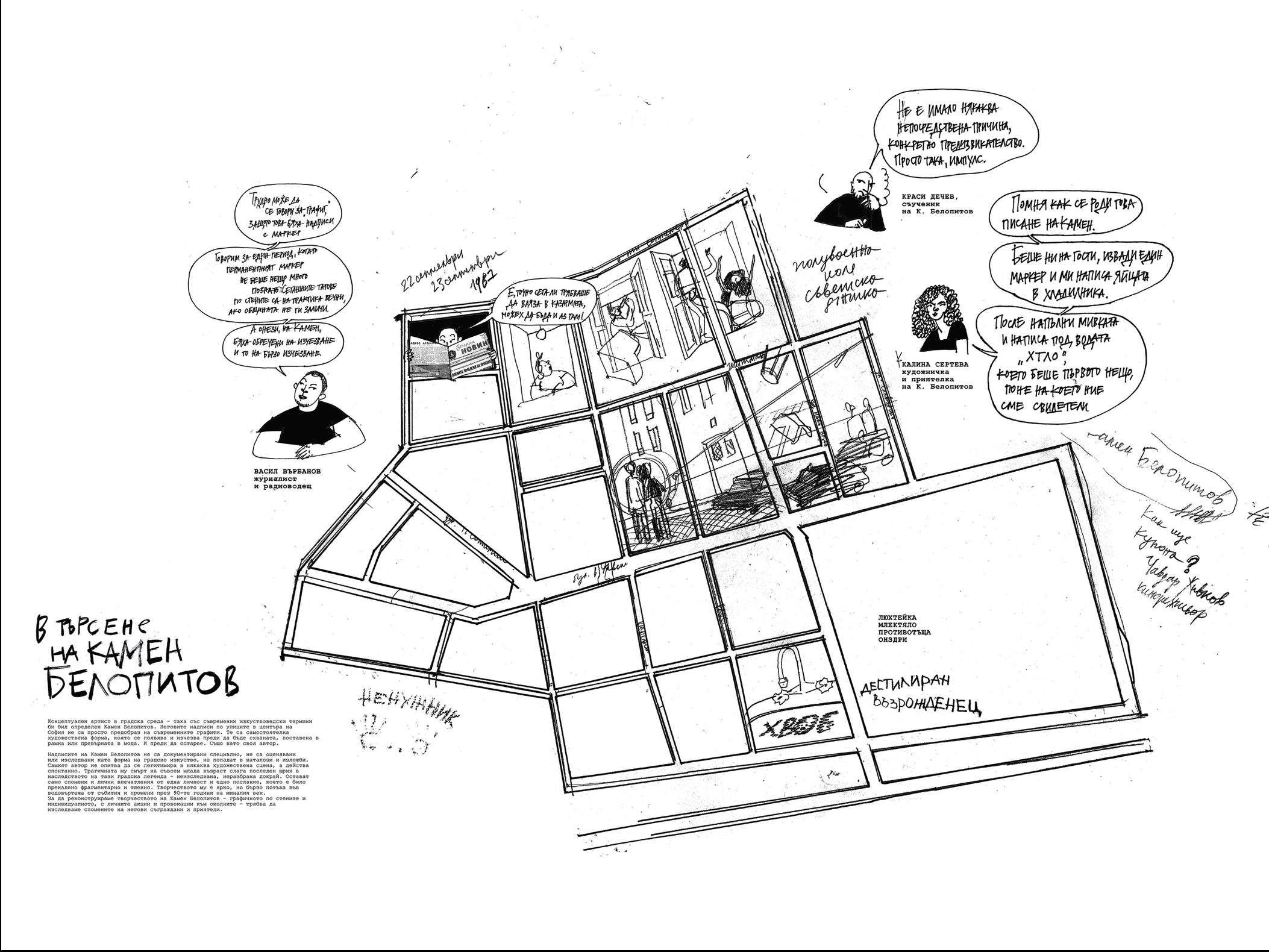

︎︎︎IN SEARCH FOR KAMEN BELOPITOV(1969–1995)

MILA YANEVA-TABAKOVA, GEORGI TENEV, 1969-1995

INSTALLATION, COMICS, TEXT

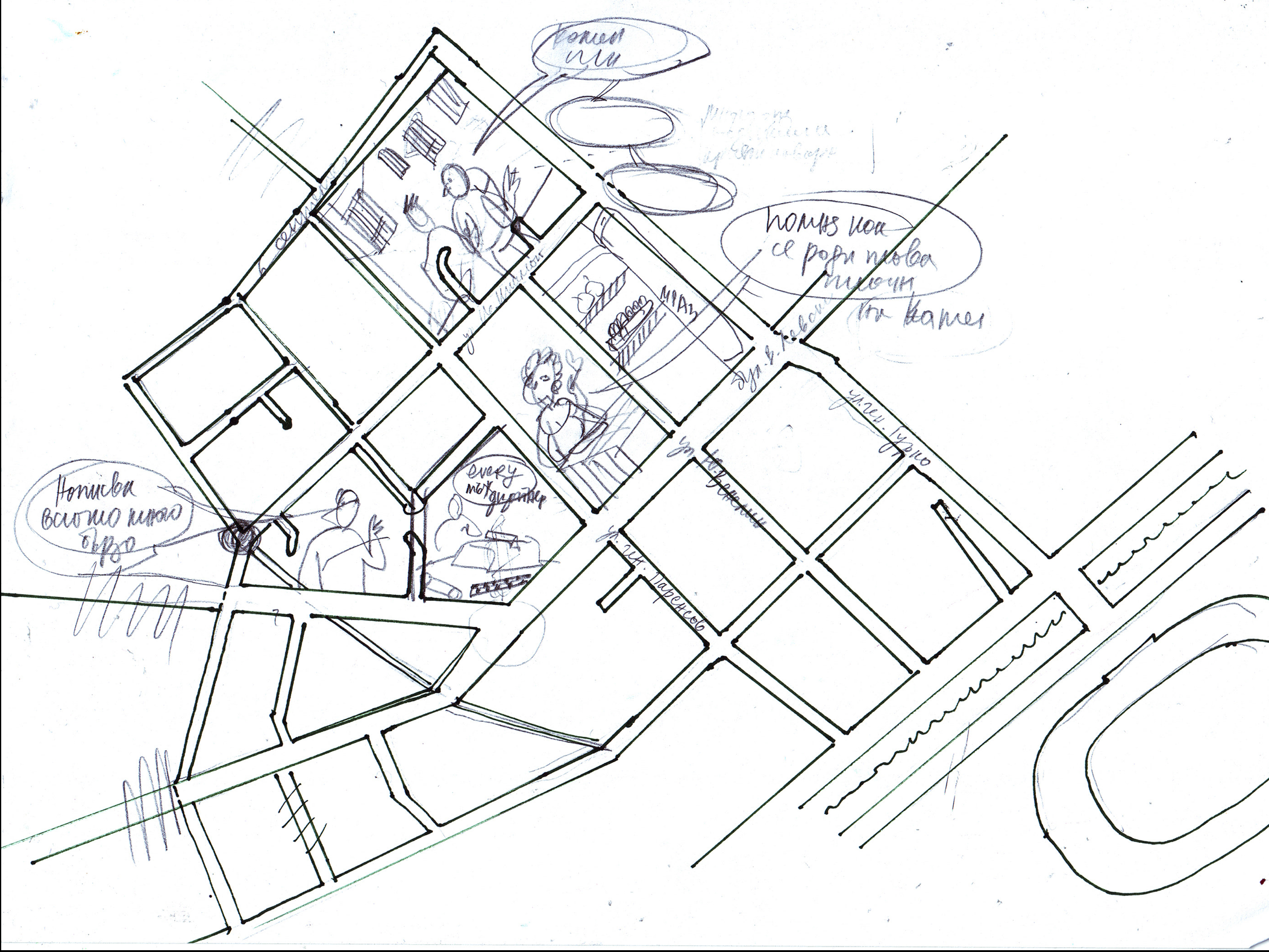

The story of a mysterious hero of the city of Sofia told through the form of the comics, contemporary street art collage and the structures of memory. Four decades after the works of Kamen Belopitov have disappeared from the streets of the Bulgarian capital, their imaginary universe is being retold on another wall in the city. This time, the latter stands in the midst of the Museum of Sofia.

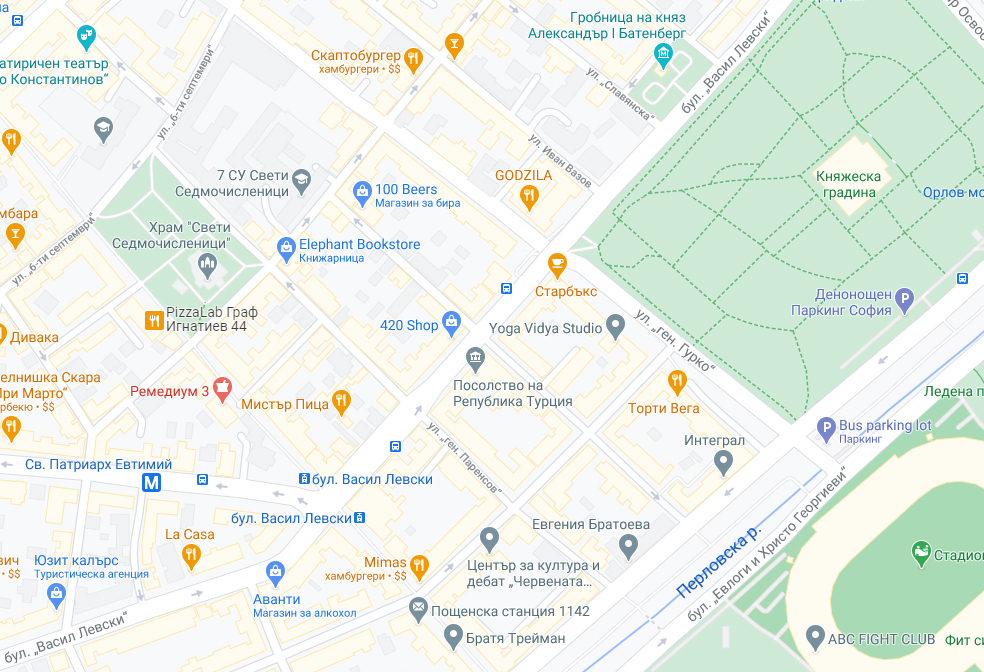

“It’s difficult to talk in terms of ‘graffiti’, as these were statements written out with a marker,” shares journalist and radio presenter Vasil Varbanov on our walk down st. Venelin where Kamen used to live at the turn with st. Shishman across 7th secondary school in Sofia. “We’re talking about a period of history when the use of the permanent marker wasn’t widespread. Today’s tags on the walls are essentially eternal unless the townhall decides to erase them. Whereas Kamen’s words were doomed, likely to be gone and rather quickly.”

“I remember the roots of Kamen’s writing,” says Kalina Serteva, artist and friend of K. Belopitov. “He was our guest, he took out a marker and scribbled across the eggs in my fridge. He filled up the sink with water and wrote beneath it the word ‘Хтло’ which was the first such writing, at least the first one we witnessed.” “There wasn’t any specific reasoning behind it, no particular challenge. It was simply an impulse.”

“Kamen came from a serious academic background thanks to his family and his parents’ careers in medicine. He was great at simulating epileptic seizures whenever he rode on the tram. People would let him have a seat.“

Chavdar Zhikov recalls, “I’ve seen how he’d jot down those tags. I’d meet him at the corner between Shishman and Grafa at 1PM. We’d stroll down Grafa, Kamen would be chatting with me and all of a sudden he’d stop, turns around and writes something down about a bread factory. He was using those markers we used to have at the time. He’d jot things down quickly before the eyes of pedestrians who had no clue what was going on. The entire area was covered with his writings. Whilst writing, he’d keep talking to me, then we’d go down to Popa where he’d wave for a taxi. The taxi would stop, he’d open the door before shouting ‘Every man designer’, then hop inside and be gone. He’d move around in that particular way.

Krasi Dechev: He was extremely intelligent. He studied at 7th secondary school and graduated with excellence. Meanwhile, he also graduated from the English college as a private student, once again with excellence. He got in to study medicine with excellent marks.

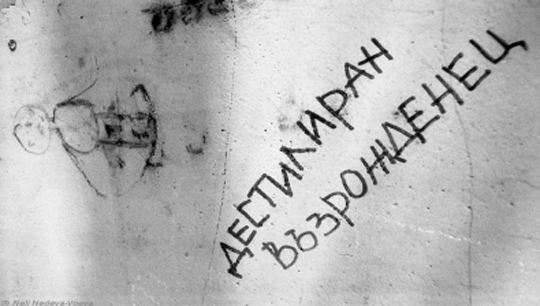

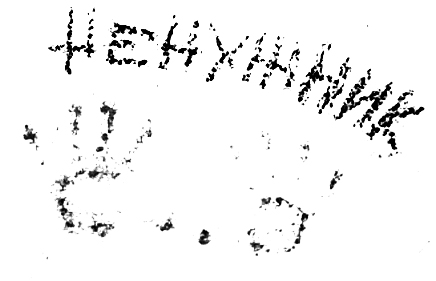

Chavdar Zhivkov: Back then in 1987-88, the mixing of Latin and Bulgarian words was very new. On the whole, his writings were distinct, they were rather unique. You would find them anywhere betwen Shishman and Grafa. I would surveille the evolution of street art, the graffiti. There have been some sad attempts at copying him years later. But he was ‘a poet on a wall’.

Vasil Varbanov: Kamen had fair hair, particular eyes, intense gaze. You would think he’s Scandinavian, German, Russian. He had a very interesting face.

Chavdar Zhivkov: I must have been in grade 8 or 9. In front of the school, this person with hollow cheeks and reddened eyes showed up and stood very closely to me. The first thing he came to say was, “And would you like me to take out your insides for them to breathe some fresh air?” In fact, he’s been very friendly - quite the opposite to my first impression of him.

Kalina Serteva: He was quite odd, he didn’t drink - at a time when every teenager drank and smoked. He was somehow quiet.

Vasil Varbanov: I’ve tried to imagine what he would be like at the present day. I struggle to visualize him... I can’t imagine him growing old.

Chavdar Zhivkov: Not long before 1989, and until perhaps 1992, there was a time when you could really feel a sense of freedom. Nothing else but freedom. Even the mafia hadn’t come to exist, there were only vague suggestions. And Kamen Belopitov’s graffiti stood as something that marked that period. It was an emergence which we hadn’t quite known before. And then afterwards, another time came when everybody would speculate about everything, even from the viewpoint of the creators. Whatever was being made would be put into a certain context. But Kamen was doing something simply meant for the wall and nowhere else, no other context or dimension. It existed by itself. Kamen wasn’t someone who would necessarily count on his anonymity, unlike most other graffiti artists whose identity is kept hidden. He was making poetry - punk, surreal and obvious.

Krasi Dechev: He was born in 1969. We studied together between 1st and 8th grade. His side of the entrance was located at the end of st. Venelin before the corner with Shishman. Our circle was unusual. The so called ‘punks’ in fact would gather at ‘Sinyoto’ (i.e. ‘The Blue’). to talk about the novels each of us had been reading.

Vasil Varbanov: I remember that on the day when I was heading off for military service, on September 22, an article was published in ‘Vecherni Novini’ (i.e. ‘Evening News’) addressed a bizarre farewell, which involved the throwing of furniture through the window, taking place at the home of a renowned family of Sofia psychiatrists. This was in 1987. The fact that something of the like was published in a newspaper was extraordinary. Similar topics were purposefully being hidden, so as not to encourage future ones. Upon reading it, I thought to myself: well, did I really have to head off for the military, I could have been there myself too! The TV show ‘LUCH’ (i.e. ‘RAY’) ran a special feature on the event.

Krasi Dechev: It was purposefully planned to happen - for the people attending that party to get arrested, to have it broadcast on TV. It was performative, a form of punishment.

Kalina Serteva: They came in jeeps. Myself and Krasi were dating, we had had a fight and had gone outside to talk in the street. When we came back, the whole neighbourhood was full of cars.

“Kamen and I grew up in the same neighbourhood. As a child, he was shy, always well-dressed, as if he had just had a haircut. It was the times, his style attracted the attention of the youth. So Kamen endured a lot of physical blows and mocking words and pranks. This went on until he grew taller and more athletic than the majority of the kids in the area to become a slightly scary and odd hero...

He wasn’t aggressive but he was in the position to defend himself and at times, other kids too. Kamen was ardent about music, certainly progressive rock (a style which for some reason was quite popular amongst us), and metal during his college studies. From then on, college life began - endless hanging and smoking, drinking beer at the corner of the Art academy and around the entire neighbourhood. There was a lot of silly exchanges which inspired Kamen’s jargon.

In fact, jargon is not quite the right word. Little by little Kamen created an entirely new world and language, through which he was able to express exactly what was going on in that world. In the beginning, this language was an amalgamation of Bulgarian words and words made up by Kamen, which bore the phonetic of the former but conveyed a certain meaning of which he was solely aware of. That phase was over quickly - the made-up language entirely took over Kamen’s speech and his stories became a complete mystery.

At the same time, he began to carry a marker on him in order to scribble notes in his language wherever and whenever. After some time, his mysterious narratives could be read across the whole of Sofia - on park benches (especially in our neighbourhood), pavillions, tram seats, street light stands etc. Over the course of a year, Kamen turned Sofia into a giant notepad, a sketchbook which contained both short anectodes as well as entire novels about the life in his imaginary world. Some of these notes were accompanied by arrows, or perhaps manuals on the location of the story’s following chapter... At least that’s the impression I got from it...

We’ve spent many evenings dominated by Kamen’s speeches, which encouraged a lot of laughter and positive emotions. Some kids even tried to decrypt Kamen’s code and enter into conversation with him. I learned of Kamen’s passing quite late, I had left Bulgaria... He was not only incredibly intelligent, but quite emotional about life in relation to Bulgarian macho mindset and attitudes. May he rest in peace!

Mila Yaneva (b. 1991) graduated from Illustration and Book Design (BA) at The National Academy of Art, Sofia in Illustration and Book Design (BA) and Graphic Storytelling (MA) in LUCA School of Arts, Brussels. Illustrator of ‘The Happy Prince’, ‘The World is Round’, ‘Maurice, or the fisher’s cot’ by List, ‘PUK!’ by Colibri. Author and publisher of the comic book ‘Souvenirs’. Co-founder of platform TI-RE.

Goergi Tenev (b. 1969) is an author, playwright and script-writer. He is the creator of conceptual projects which make use of archives, individual memory and XXth century political history. Writes and records portraits of contemporary visual artists.

Goergi Tenev (b. 1969) is an author, playwright and script-writer. He is the creator of conceptual projects which make use of archives, individual memory and XXth century political history. Writes and records portraits of contemporary visual artists.

© History in Between, 2021This project is part of the Cultural Calendar of Sofia, Ministry of Culture and Sofia History Museum.

Connect:

︎ ︎ ︎

„История помежду“ ("Проект за музейни намеси в РИМ, София") е съвместен проект между Фондация „Изкуство – Дела и Документи“ и Регионален исторически музей, София, подкрепен Календар на културните събития на Столична Община.

History in Between (Project for interventions in the Museum, Sofia) is a collaboration between the Art Foundation - Affairs and Documents, and the Regional History Museum of Sofia. It is supported by the Calendar of Cultural Events of Sofia City.