︎︎︎

EXCAVATING THE PSYCHE

JULIAN CHEHIRIAN

INSTALLATION, RESEARCH

PANEL 1 - Introduction

In 1963 a young woman in Gabrovo was experiencing a crisis. At home her parents observed erratic behavior. At work colleagues noticed frequent errors, absences and an unexpected change of character. She fell out of communication with her friends. Soon she was sent for examination to a psychiatric hospital.

PANEL 3 - In This Exhibition

In 1963 a young woman in Gabrovo was experiencing a crisis. At home her parents observed erratic behavior. At work colleagues noticed frequent errors, absences and an unexpected change of character. She fell out of communication with her friends. Soon she was sent for examination to a psychiatric hospital.

My question, and the organizing inquiry for this exhibition, is the following: at this particular time in Bulgarian history, what was the horizon of possibility for a person in distress to gain an understanding of their experiences? What social, cultural and scientific models existed through which a person could achieve clarity about a divergence from typical and coherent personal experience?

This exhibition explores the consequences of the availability or unavailability of particular ways of deriving meaning about our interior worlds in moments of crisis and destabilization.

Human’s relationships with social understandings of the healthy and sick body and mind demand our awareness of how in different moments and by different people, the mind and body have been conceived of and approached differently through transforming social, cultural and scientific frameworks.

PANEL 3 - In This Exhibition

I first studied the development of psychiatry in Bulgaria in archives and libraries with a particular interest in its transformation during the communist period. In these repositories there is much to be learned about ministries, institutions and the politics of the psychiatric profession. Critically absent from those materials, however, is the psychiatric subject: the individual incrisis who came into contact with psychiatric institutions and practices. Constantly returning to that individual has been the most interesting aspect of my work. I conducted interviews with psychiatrists and former patients in order to understand some of the clinical and existential consequences of the imposed Soviet model (of the suppression of nonphysiological approaches to diagnosis and care). This began to open views towards a ‘human’ or ‘social’ (rather than merely an institutional) history of psychiatry. This exhibition lays modest foundations for interpreting these historical horizons by showcasing methods for reconstructing the fields of possibility that existed for mentally ill individuals at this time. It uses two methods to present two directions of my work. A material history approach arranges unseen photographs of psychiatric institutions and a progression of texts embodying concepts and practices disseminated by pedagogy and psychiatric scholarship. Through them we cannot understand the interior world of a patient. However, we can study how generations of Bulgarian practitioners were trained to conceive of and diagnose the interior world of ill or abnormal individuals. The second method is an installation that approaches the absence of artifacts about individual’s experiences with psychiatry through a speculative reconstruction of a consultation during the peak of the Soviet model’s reign (1950-1975).

PANEL 2 - The Soviet Model

In 1950, a ‘Pavlovian teaching’ was decreed as the only scientific approach to the study of human psychology and the treatment of mental illness by the Soviet Academies of Medicine. The subsequent imposition of the Soviet model in Bulgaria resulted in the medicalization of atypical human experiences and a practice of treating patients predominantly by physiological means.

This event punctuated a period of Bulgarian history (1888-1944) that had brought an extraordinary diversification of theories and methods for treatment of the mentally ill. In the decades following Bulgaria’s independence from Ottoman rule, hospitals were modernized and medical students studied abroad in Europe, bringing the latest innovations in psychiatry, neurology and psychoanalysis. The Pavlovian teaching corresponded to the materialism of Soviet ideology and instigated the suppression of alternative theoretical and therapeutic frameworks. From the 1950’s and onward the body became a predominant locus and medium for the psychiatric analysis and treatment of divergent human experience. The outlaw of private practice and individualbased psychotherapy led to a widespread institutionalization of humans in distress. As the mind or psyche faced rejection as a meaningful therapeutic locus, bodies were left to speak out through their diagnoses: medicalscientific representations of an interior world that could no longer be read.

The inner worlds of individualsincare were approximated through empirical studies of the biological and physiological registers of their illnesses. The body became a

surface as the analysis of physical and behavioral symptoms replaced contextual and narrative based approaches to understanding the suffering of individuals.

Under the Soviet model patients became empirical objects for psychiatric science. Diagnoses became personifications - representations of the inner world of the individual. There were insufficient frameworks for social reintegration and many hospitalized patients who were capable of autonomous existence would live out their lives in isolation and dependence. This occurred in a psychiatric paradigm that conceived of mentally ill individuals as pathological entities to be managed rather than humans to be treated and reintegrated into society.

Pre-liberation & Modernization

Prior to its liberation from Ottoman rule Bulgaria did not have significant national infrastructure for the care of the mentally ill. How was mental illness was conceived of and treated during this period? Potential leads are Богомилците and баяне. In Melnik there is a church called Св. Антони with

handcuffs attached to a central column. Individuals with psychological problems, nerve issues and

demons would be left chained in the church overnight beneath the watchful eye of Christ. It is known that therapeutic practices included prayer, baths, music and herbal treatment in monasteries, churches and mosques.

In 1888 the establishment of the first well organized psychiatric clinic at the Александровска Болница

initiated a period of aggressive modernization. The improvement of facilities was complemented by the import of theoretical models and clinical methods by students studying abroad in Germany, France and Austria. The psychoanalytic tradition attracted the interest of Bulgarian practitioners. During WWII

diagnostic and therapeutic methods resembled those practiced in the rest of Europe; “the full arsenal of psychiatric therapies of the period was applied: sedatives, hypnotics, biological and chemical

therapies, antibiotics, electroconvulsive therapy, worktherapy, and psychotherapy. In addition to experimental and pharmacological treatments, various forms of psychotherapy were widely applied, such as rational, suggestive, hypnotic, and psychoanalytical therapy” (S. Milenkov). Prior to 1944 there was a psychoanalytic group in Sofia and vibrant intellectual exchange with the European

community.

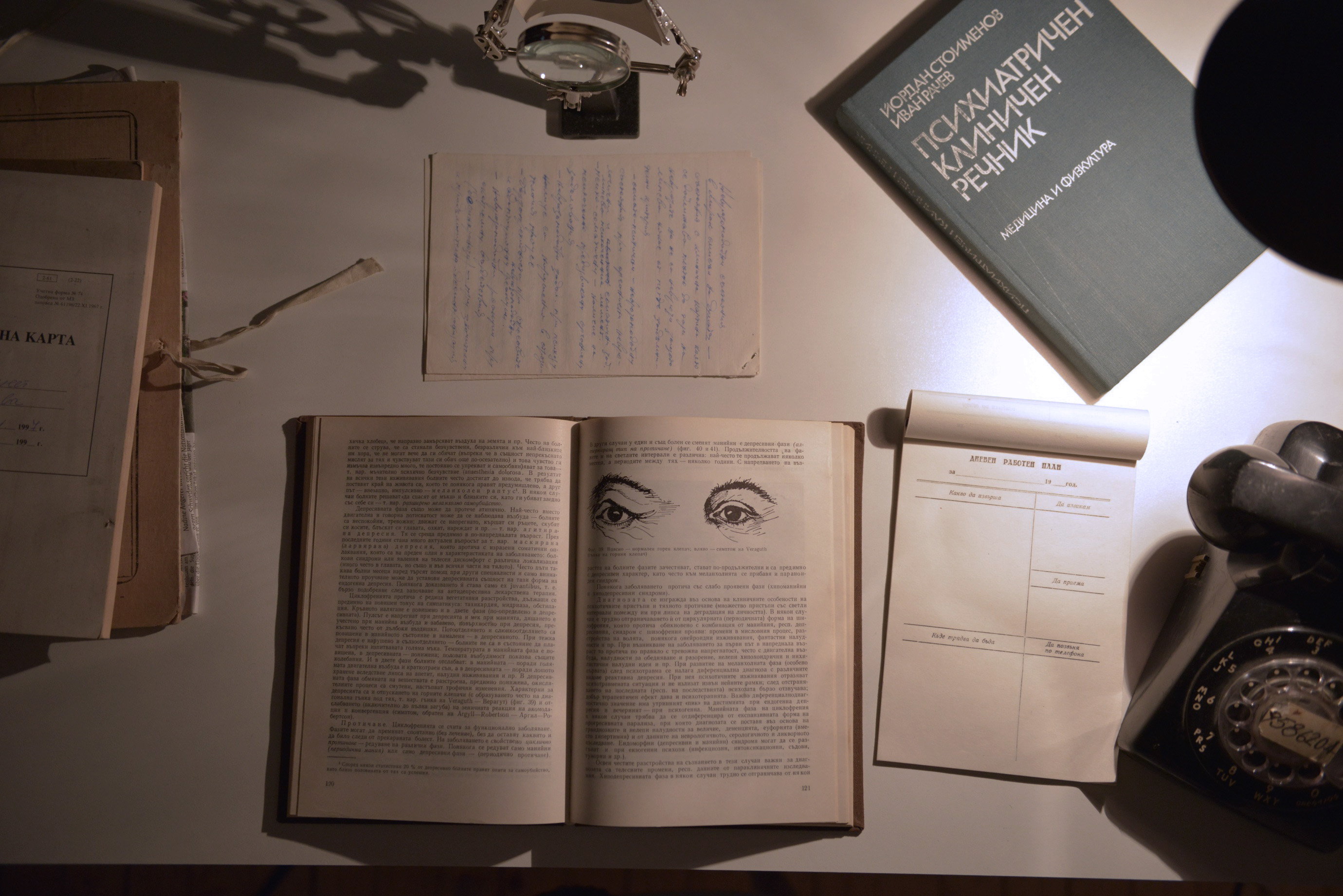

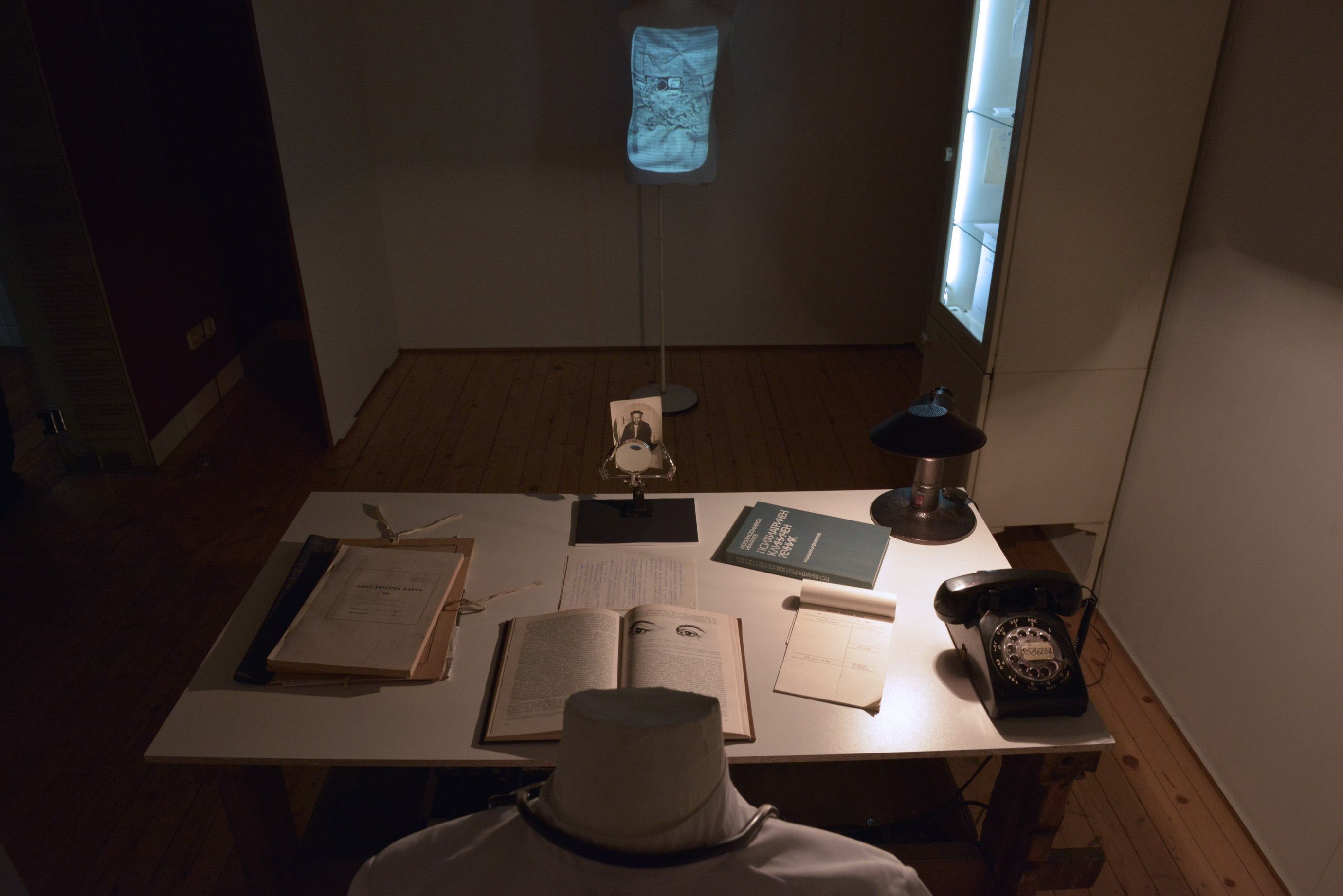

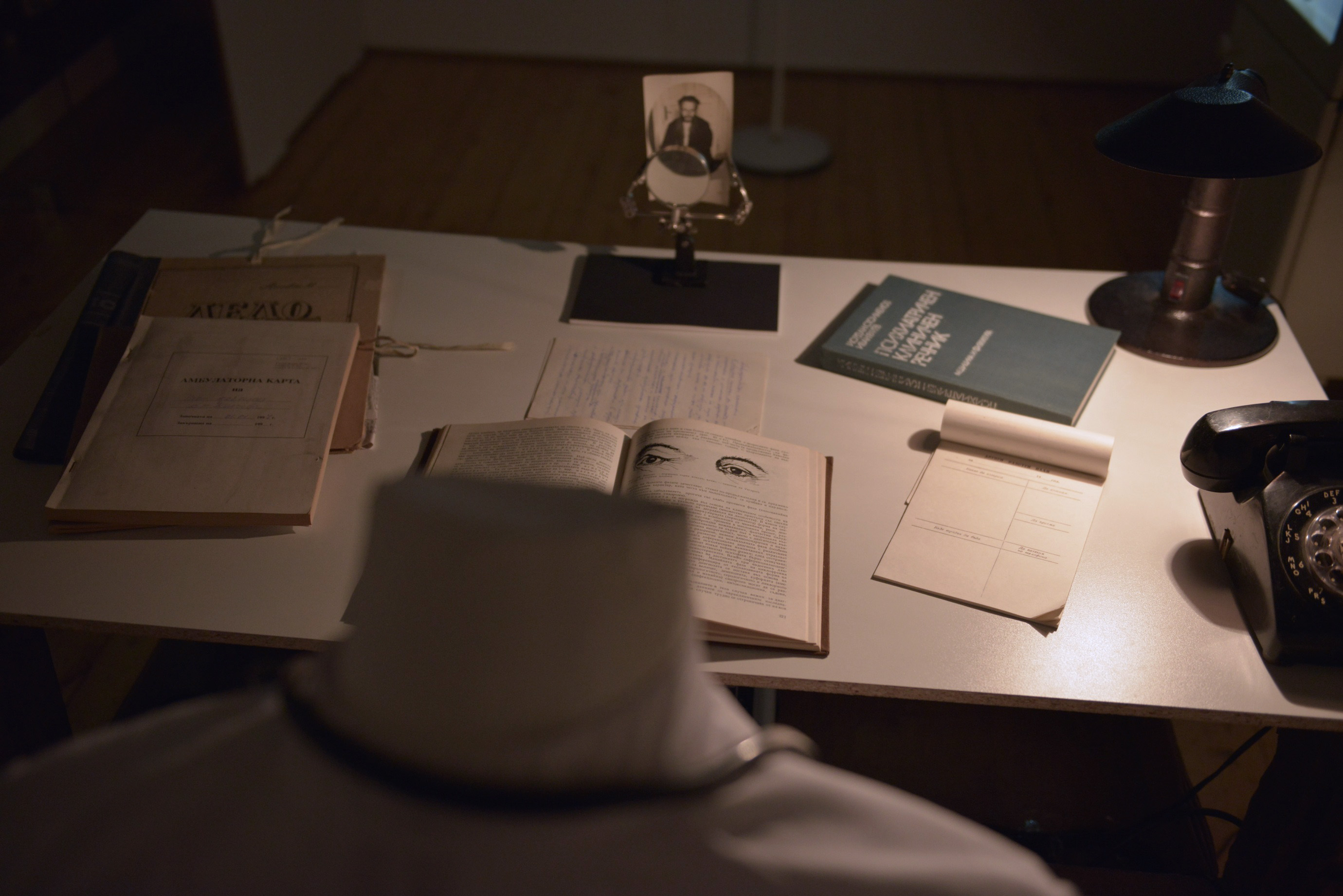

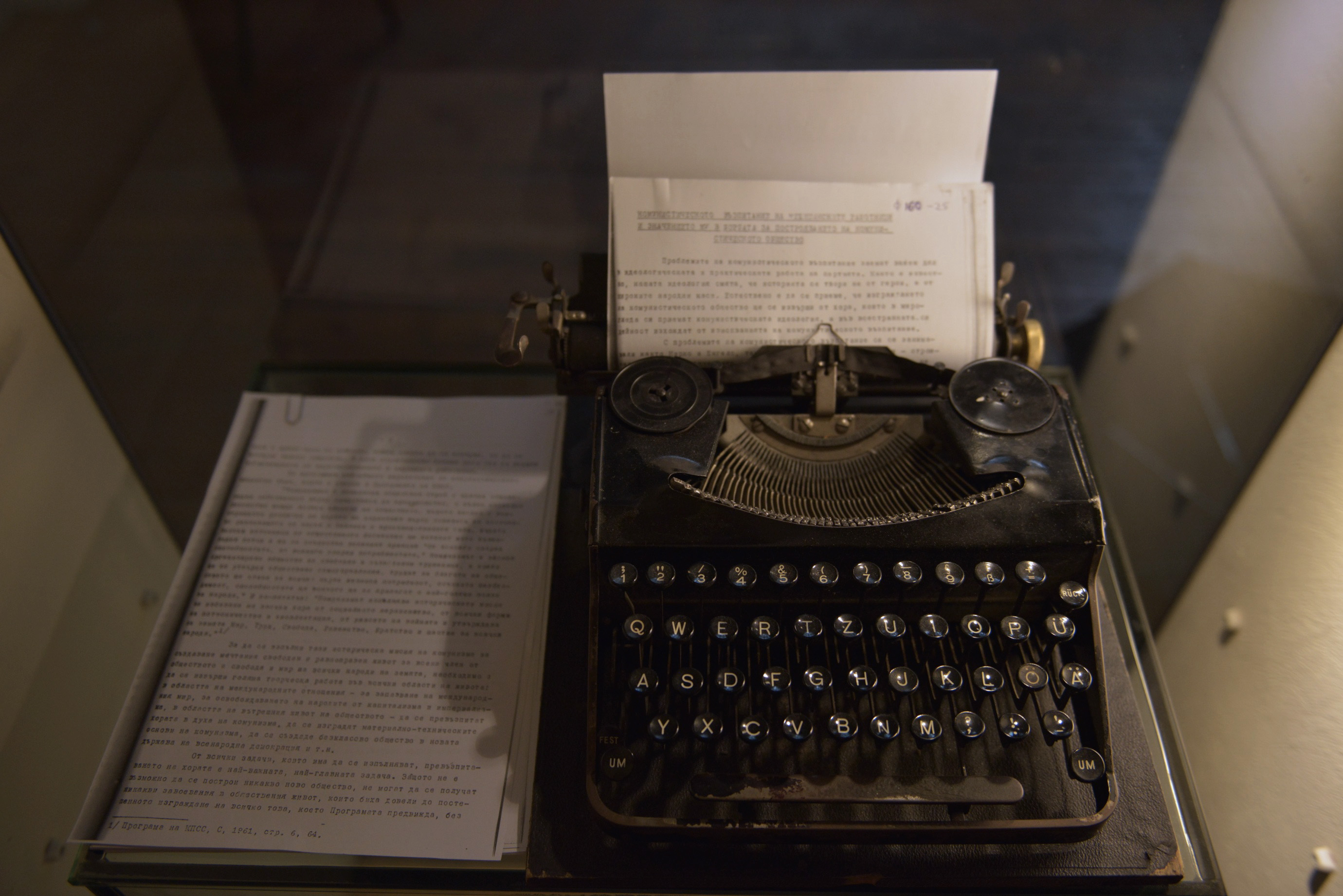

The space behind this wall interprets an exchange between a psychiatrist and patient during a

consultation. In this scenario they have appeared for a consultation at a psychiatrist’s office in a Bulgarian polyclinic during the 1950’s, 60’s or 70’s. During this period of time consultations were

restricted ten minutes. This standard remains in place today at the здравна каса. In psychiatric consultation the interior world of the patient is analyzed and approximated within frameworks of abstracted clinical knowledge. This process collapses the fluctuating life of the patient into a stable and legible form that is fixed in the time and space of the session. Identified symptoms and resulting

diagnoses can become referents for their troubled experiences and form new parameters for

selfunderstanding. This phenomenon can result results in the personification of diagnosis; in this way,

first person experience and its psychiatric enframing are collapsed into one.

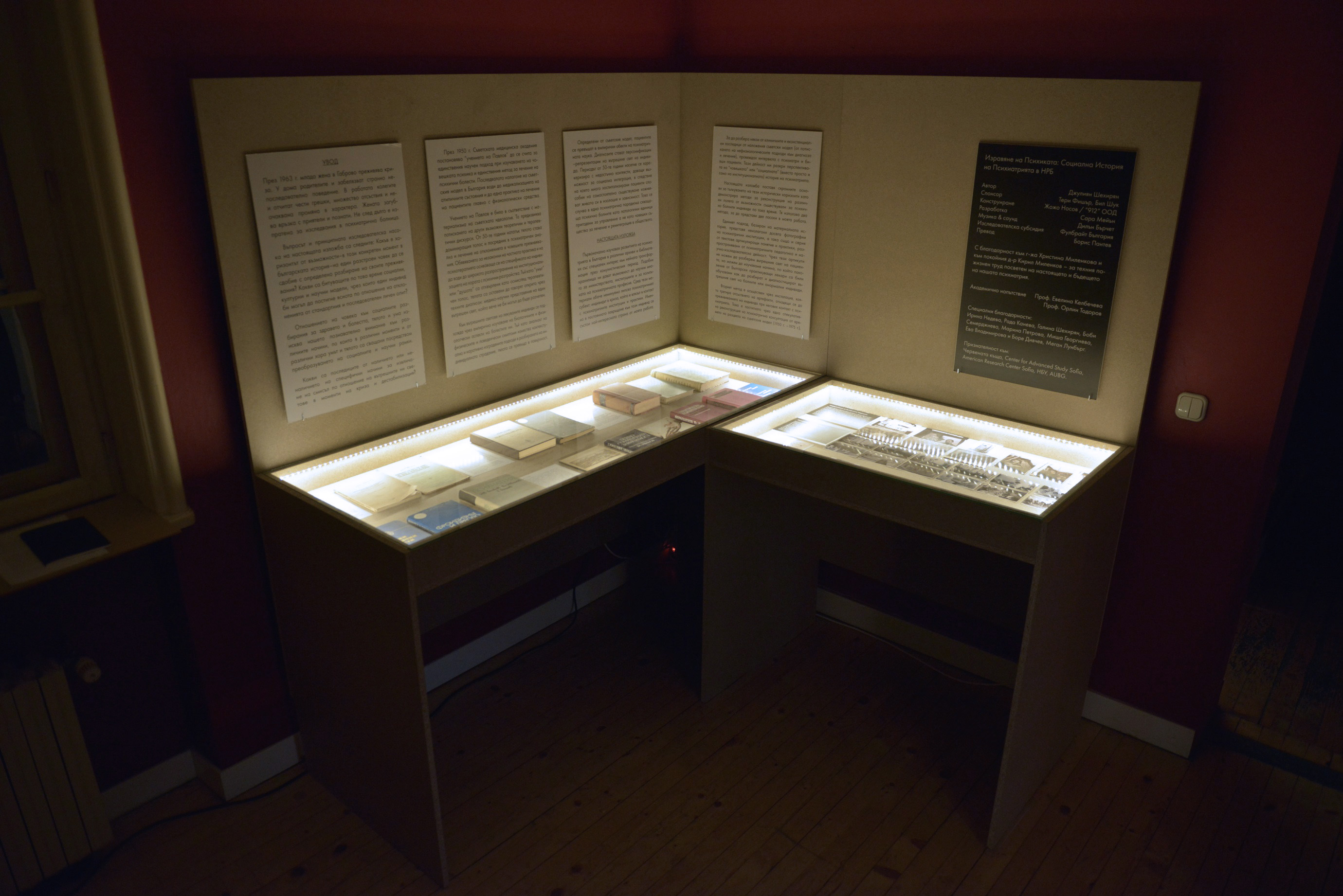

The first group, from the 1930s, has its probable origin in a doctor’s collection of photographs. These

images are of great historical significance. They detail the modernization of Bulgarian medical facilities and services in the first decades following Bulgaria’s liberation from Ottoman rule. In the selected

photographs we can see diagnostic identifications of congenital and thyroidinduced mental disorders.

These are significant as they raise questions about the individual and social experience of mental

illness and atypical development during this period.

The second group has its origins in the cameras of hospital photographers of the 1960s. Through these we can better conceive of Bulgarians whose lives unfolded inside of the walls of psychiatric institutions -especially those in Karlukovo and Lovech. There are scenes of worktherapy,

a significant outlier to the dominant pharmaceutical approach. The images are striking in their depiction of the social and communal experience of the individuals receiving care in these facilities. These photographs

are present in this space due to the unique scholarly efforts of the late Dr. Kiril Milenkov - a

distinguished psychiatrist who devoted a significant period of his late career to the historiography of psychiatry in Bulgaria.

The final group of images is sourced from a 1973 textbook on psychiatry by Temkov, Ivanov et. all, an

edition of which is visible in the collection exhibited below. In these photographs individuals are

visually extracted from the social environment of the hospital. Qualified by diagnostic terminology and taxonomic elaborations, they have radically been transformed into objects for a psychiatric science.

1944

The new communist leadership centralized medical services. It outlawed private practice and purged hospitals and medical universities of politically questionable individuals. , exhibited below, catalogues the killings and repressions of doctors and medical students (see K. Milenkov below). Many were

stripped of their ability to continue their professions or to become practitioners. This sanitizing of the medical community fortified the position of the Communist party in professional circles, emboldening partymember psychiatrists to harass colleagues with ideas diverging from MarxistLeninist

ideology (e.g. Nikola Shipkowensky). Psychoanalysis was subject to an ideological rejection. When it was

mentioned it was in a critical light. Academic and scientific exchange with Western Europe was rerouted

to the USSR. Infrastructure and access to care was improved for provincial areas. In attempting to align psychology and psychiatry with MarxismLeninism, mental illness was theorized in

paradoxical ways: as inheritance of capitalism (with neuroses and depressions), or as a physical deformation that could be shifted through physiological intervention (as with heavier deformations or deviations from the norm).

The Soviet model and beyond

The Soviet psychiatric model was introduced in Bulgaria in the 1950’s. See description on exhibition

panels above. The exclusivity of this biophysiological model remained mostly unchallenged until the early 1970s. The literature in this section begins with a 1952 Pavlovian anthology and illustrate the

alignment of psychology, psychiatry and neurological science with the recently introduced Soviet

model.

The first conference on psychosomatic medicine was held in the late 1960’s. Psychiatrist Dr. Aleksi Alekseev held the opening speech, addressing how psychological process affects physiological process.

This view was incompatible with Marxist materialist dogma and he was severely criticized by dialecticians for adopting allegedly Freudian and American ideas. Dr. Georgi Koychev notes that a series of symposiums was held in the 1970’s in Danube nations. Although much of the insights culled from these meetings dissipated quickly, the gatherings stimulated a gradual introduction of group

therapy methods in Bulgaria. During the same period, individual based psychotherapy was practiced in secret after working hours by a small circle of clinicians led by Dr. Hristo Dimitrov. Initially

commissioned to produce criticisms of psychoanalysis, some practitioners went on to train in the discipline or emigrate and practice abroad. The translation of existential literature by authors including Sartre and Camus influenced some psychiatrists to write about the existential context of mental

illness. See “Etudes of a Psychiatrist” by Todor Stankuchev. “Практическа Психотерапия” indexes a radical diversification of acceptable therapeutic modalities, bringing together articles by on suggestion and hypnosis, catharsis, rational, group and family psychotherapy, as well as a rehabilitation oriented

sociotherapy framework. This clinical and theoretical flourishing signaled the end of the Soviet model’s exclusivity. In 1990 “Introduction to Psychoanalysis” by Freud was published once again in its

original form.

I. D

EVELOPING THE SUBJECT

EVELOPING THE SUBJECT

The installation does not begin with the consultation itself but inside of the individual. There we can observe the emergence of an interior worldwatercolor paints and pen strokes create a personal

landscape that is paired with symbolic melody. As the body and psyche are elaborated their representation becomes increasingly cohesive, unified and ordered.

II. Trauma emerges

In this stage the coherence of the person’s interior world is threatened. Traumatic zones emerge,

stagnate and fester, taking form as knotted textile layers. Established rhythms and melodies become dissonant. An increasing disorder has diminished this individual’s ability to make sense of themselves.

The person, now incrisis, looks outward and beyond themselves in an effort to understand what is no longer understandable.

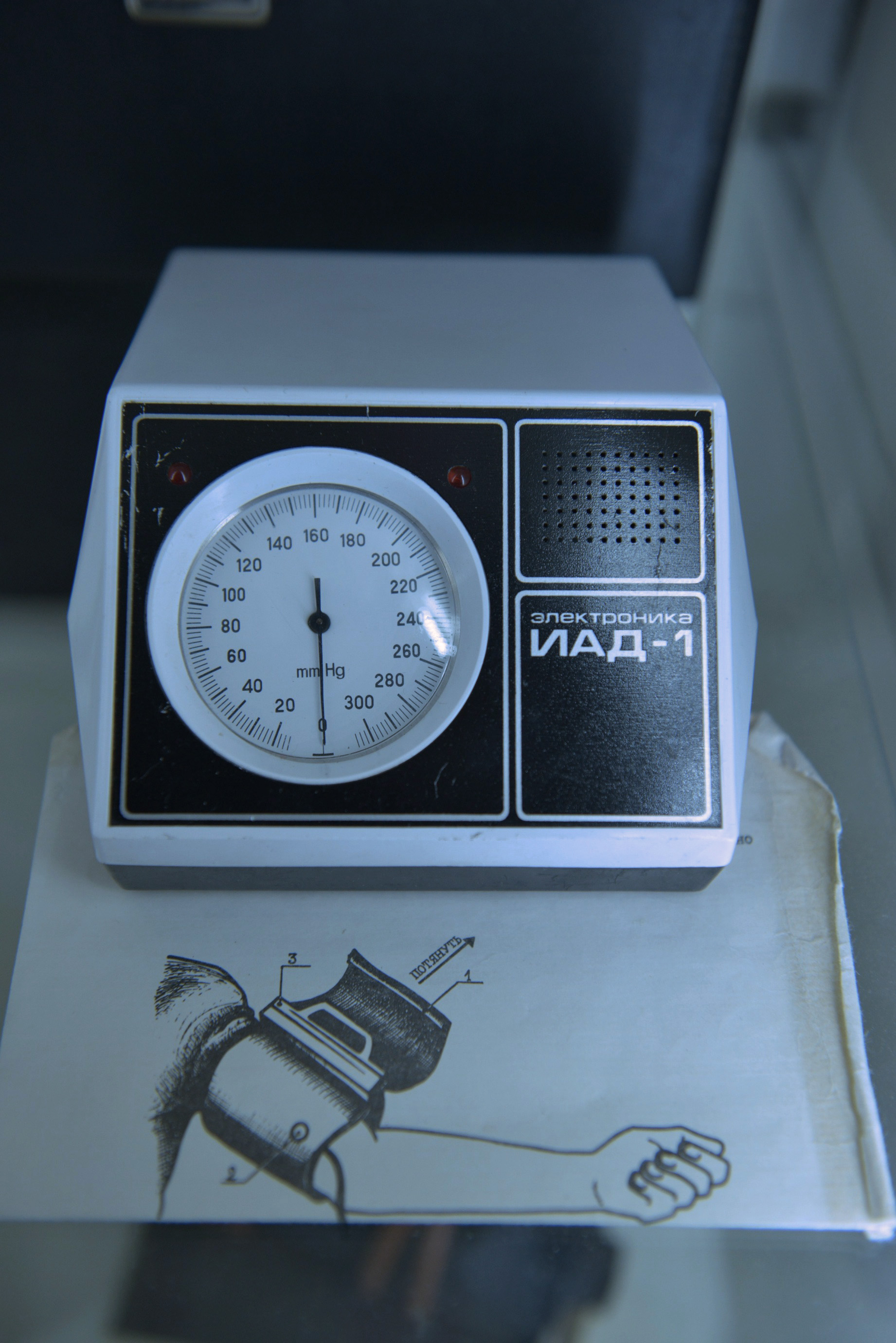

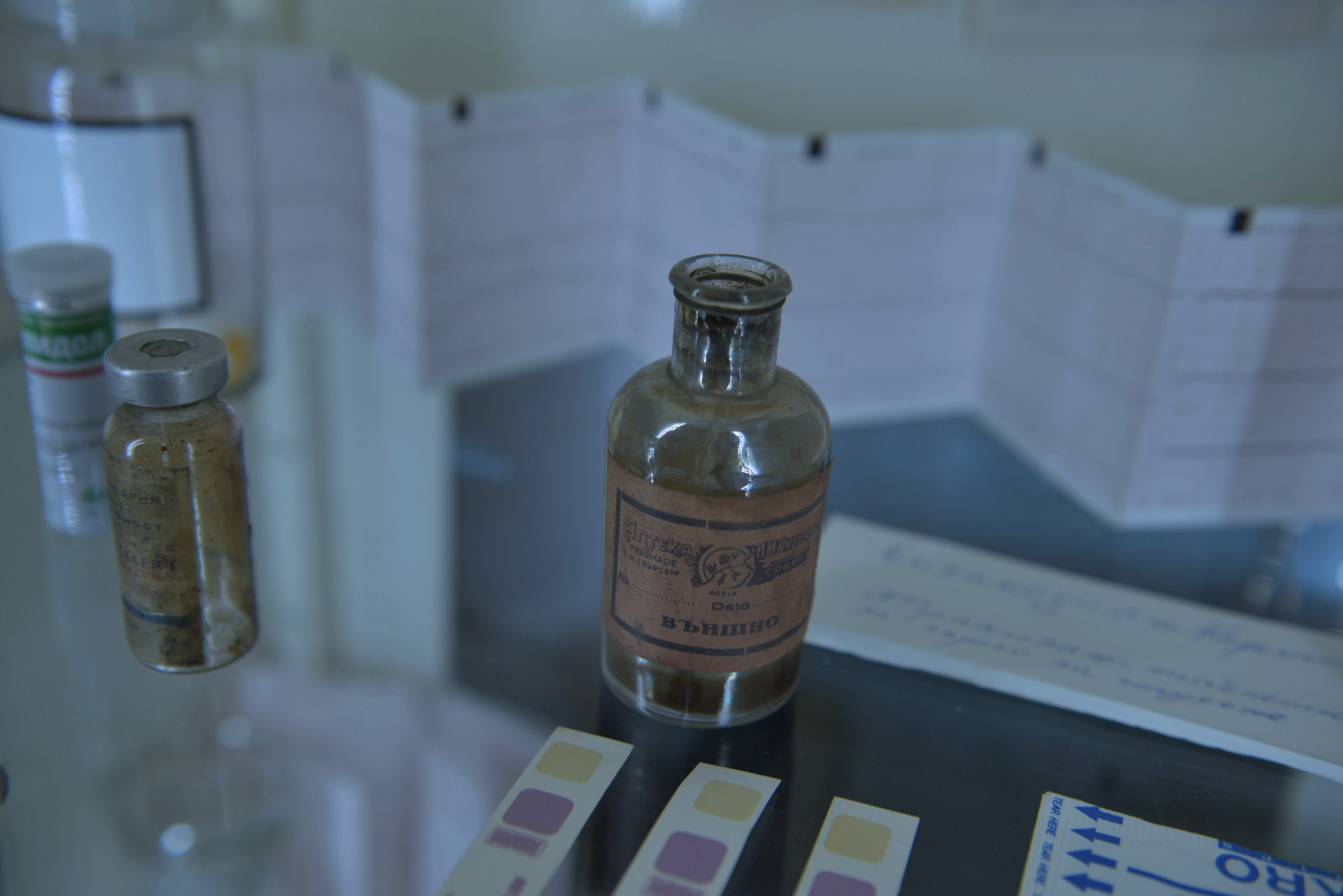

III. PSYCHIATRIC CONSULTATION

The interior world of the patient is analyzed. Visually, a matrix is overlaid like a surgical blanket atop

the patient. The sounds of the medical environment begin to cut through and manipulate the melody of the subject’s inner world. A pathological locus is identified and a delimited area begins to be worked

upon. We can hear sounds of the medical cabinet and instruments whose purpose is to measure the

body, to reveal and to shift its state. The clatter of pharmaceuticals, blood pressure meters and glass vials is punctuated by the sound of an opening and closing cabinet door. Piece by piece, the material

of the trauma is exposed, pinned, and trimmed away. The examination is sensitive only to the

material etiology of the problem. This is indicated to us by the opacity of the surgical sheath. We are still able to see the unabstracted trauma beneath.

IV. AFTER THE CONSULTATION

The consultationmatrix has been removed, and the patient has internalized the diagnosis. While this results in the relative stabilization of the sound, the patient’s melody is wilted and skewed from its

original form. Pins remain as artifacts of the analysis. And although the traumatic zone identified during the consultation phase has been removed, its persistent roots remain visible once the diagnostic grid is removed. This references how an exclusive focus on the physiological dimensions of

the illness (without an excavation of its subjective, existential and embodied context) fails to achieve a sustainable and integrative therapeutic resolution.

Julian Chehirian is an artist and a PhD candidate in the History of Science at Princeton University. In his artistic research practice, he applies historical and ethnographic methods in multimedia installations and exhibitions which examine intersections of the mind sciences, memory, and culture. His projects have been shown in solo exhibitions in Washington, D.C. and Sofia, Bulgaria.

© History in Between, 2021This project is part of the Cultural Calendar of Sofia, Ministry of Culture and Sofia History Museum.

Connect:

︎ ︎ ︎

„История помежду“ ("Проект за музейни намеси в РИМ, София") е съвместен проект между Фондация „Изкуство – Дела и Документи“ и Регионален исторически музей, София, подкрепен Календар на културните събития на Столична Община.

History in Between (Project for interventions in the Museum, Sofia) is a collaboration between the Art Foundation - Affairs and Documents, and the Regional History Museum of Sofia. It is supported by the Calendar of Cultural Events of Sofia City.