︎︎︎OPERATION “THUNDER”

KRASIMIRA BUTSEVA, 2020

PHOTOGRAPHY, VIDEO, PERFORMANCE, INSTALLATION

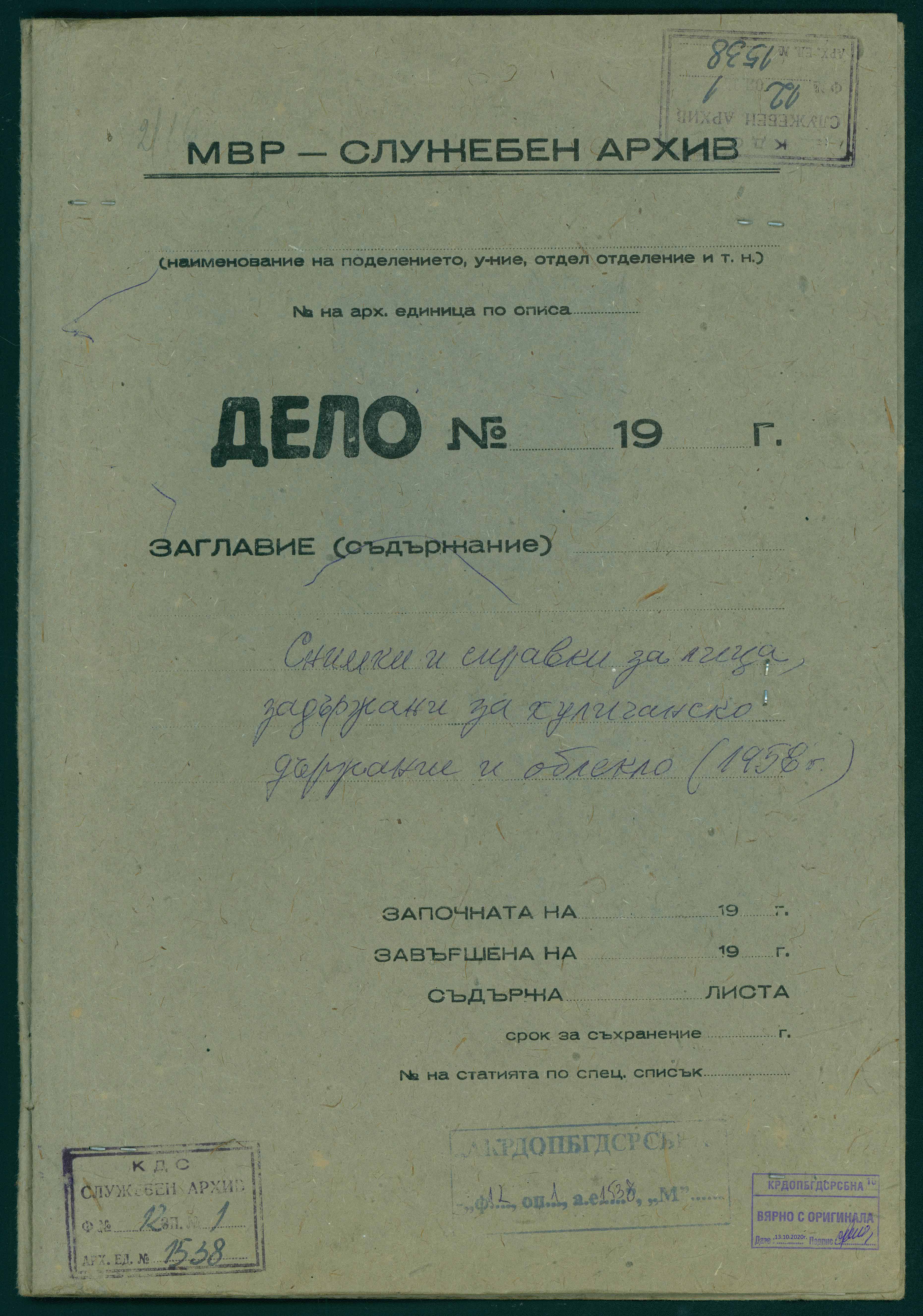

In 1958 the Bulgarian State Security led operation “Thunder” in which 1328 young people from Sofia were arrested, as they wore skinny trousers, short skirts and duffle coats, and listened and danced to Western music. Most of them were between 20 and 30 years old and were artists, musicians, writers and university students. They were detained in the first department of State Security which was dealing with the investigations of political crimes, and was on Moskovska №5 st.. They were consequently sent to forced labour camp Belene.

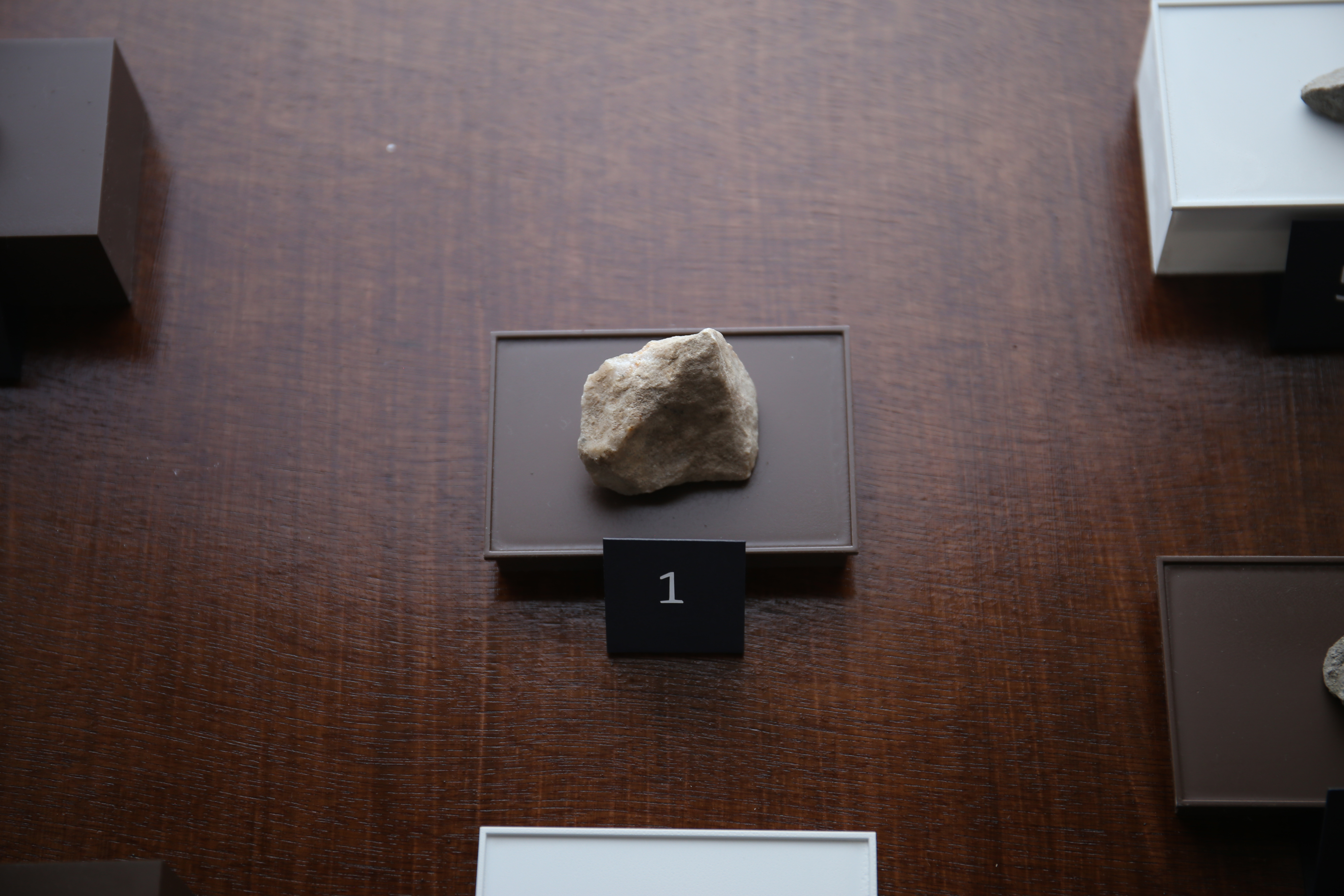

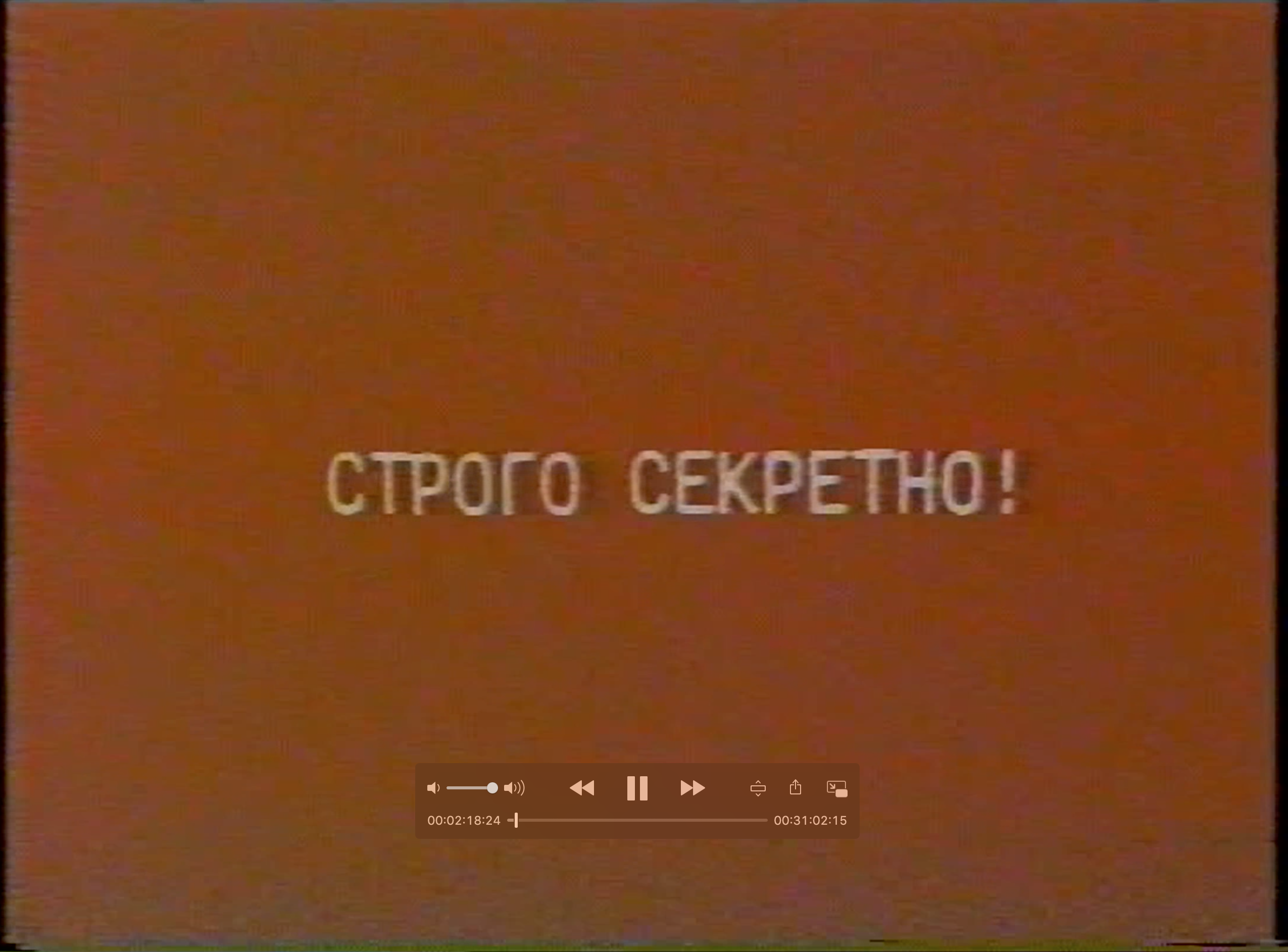

Operation “Thunder” is a site-specific multimedia installation commissioned by for Sofia History Museum. A section of the work features archival photographs of the people arrested and photographed in the State Security’s investigation department. There are also three moving image pieces, in Moskovska №5 I have combined photographs taken at the site with an essay about the history and present of the building. The hands of the curator is a performative film in which I bring in and curate artefacts collected from the site of State Security in the museum space. In Top Secret! I have employed footage from the State Security archives used for the training of secret agents. The installation also conveys elements from the interior design of the offices of State Security.

The installation attempts to pose questions regarding the memory of buildings and spaces, and how to preserve and activate it.

Part 1: Moskovska 5

The building was designed by the architect Asen Mihaylovski in 1937, and was built between 1938 and 1939. Initially, it housed the insurance company “Generali”. During the WWII, a branch of the company “Bayer” moved in the building. After the nationalisation in 1947, the Ministry of Interior moved in, and a part of it was occupied by State Security’s investigative department. This specific department (after 1952 called First Investigative Department) dealt with the investigation of any “political offences” against the communist regime – from “spying” and “illegal activities” to telling political jokes, all of which was incriminated as “foreign and enemy agitation and propaganda”. The basement of the building was turned into a cell block and the former prisoners recall numerous cases of violence.

In 1972 the administrative departments of the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party moved in the building. During these years a renovation of the basement took place and the cells were obliterated. Survivors’ accounts indicate the existence of two floors with cells, not only one. Since 1992 the building is used to house the Central State Archives.

In 2011, Dr Martin Ivanov, the chairman of the Central Archives suggests the creation of a museum inside of the former cells. The museum had to recreate the activities of State Security – with the restoration of the cells, and through documents and objects from the archives. The new museum had to open within a year. But it is never realised there or elsewhere in the country. In present day, there is still no institution narrating the history of the political violence of the communist regime.

Part 2: The photographer & the subject

In two out of 52 photographs, the subject has turned their eyes towards the camera.

The pupils are gazing at the photographer, who is pressing the viewfinder to his face. Silence and stillness – only the index finger presses the button. A sudden noise cuts the room. The flash freezes the bodies for a fraction of a second.

S.K. is a student at the University of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering in the capital. Her father works in the Ministry of Interior’s restaurant “Light” and her mother is a housewife.

She holds her eyes onto the glass – in disagreement and dissent. Her mouth is slightly open as if in conflict, and her eyebrows are raised. She stares at the camera, at the photographer with confidence. She is ready to show and prove her rights. The wallpaper behind her is made of little figurines, and the floor is covered with parquet.

A.S. is born on the 20th of August 1927. She works as a geologist. Her father is retired, her mother is a housewife. A.S. is not married, nor sentenced before.

She has turned towards the lens – she is in front of a white wall, the lamp switch is on one side, next to the door frame. On the floor there is a wooden covering. Her hands are locked in front of her body, she holds a bag, pressing it with force to her stomach. Her eyes carry the gaze of a child – sweet, tender and complying. Such which suggests that one has been convinced of their fault, and one charged with shame and fear.

She is still, standing next to the wall – obeying to the authority of the room, the authority of the photographer, the one carried by the apparatus and most of all the one of the agents.

When asked, she turns her body to 180 degrees and remains still. The lens captures the same space as before. But not her gaze. She stays in the same pose, with her hands and bag in front of her, as if she is just slightly moved. Stains and splashes cover the second photograph. Black and white rain is falling on the wall, and moves to her body and then to the thin curly frame. The photograph is damaged. Fragments of the small image, big as a palm, are obliterated, missing.

These damaged or rather bad images are wrecked by violence and history. They are not allowed and remain perplexing and unconvincing, as of the neglect, political denial and as of the destroyed evidence and archival files. The bad images cannot give a full account of the situations, which they represent. But if what they attempt to represent is otherwise obscured and dim, then the conditions of their visibility are exponential. These photographs are excluded from the legitimate discourse and from turning into facts. They continue to be subjects of indifference and repression.

These anthropological portraits aim to classify them, to fit them in the frame of criminals and hooligans. These silent images, silenced by the regime, are everything but quiet. They pulse on different and lower frequencies. And to be heard they need to be seen, they need to be looked at continuously. As their pauses and stillness are extremely loud.

Part 3: The hooligans

The anti-communist revolution in Hungary during October and November of 1956 resonated across the whole Soviet bloc. In Bulgaria, State Security noted a rise in the “anti-governmental activities” across the young generation, in the form of criticism towards the regime, fleeing or attempting to flee to capitalist countries, establishing anti-communist groups, protests against the ideological subjects in higher education and the compulsory studying of Russian language, appeals for democratisation of the public and university life, remarks against the system by Bulgarian students in the USSR and other forms of protest.

The anti-communist revolution in Hungary during October and November of 1956 resonated across the whole Soviet bloc. In Bulgaria, State Security noted a rise in the “anti-governmental activities” across the young generation, in the form of criticism towards the regime, fleeing or attempting to flee to capitalist countries, establishing anti-communist groups, protests against the ideological subjects in higher education and the compulsory studying of Russian language, appeals for democratisation of the public and university life, remarks against the system by Bulgarian students in the USSR and other forms of protest.

In the beginning of 1958, the mass arrests began. They were a part of “Operation Thunder” led by the Ministry of Interior. This operation was suggested by Todor Zhivkov, the first secretary of the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party, and led by Mircho Spasov, who was the vice-minister of the MI and was a head of State Security and the forced labour camp “Belene”.

1328 individuals were arrested in Sofia. The majority of them were writers, artists, musicians, anarchists, people who were in touch with individuals from Western countries, others from families who were declared as “enemies of the people” or “ex-people”, or some who told political jokes or criticised the system.

The majority were between 20 and 30 years old. In a report by State Security it is stated that these were “mainly young people from the new intelligentsia, students in art universities – singers, ballet dancers and other people of the arts.” Organised troops of the Ministry of Interior conducted arrests on the streets of individuals wearing skinny trousers, short skirts or duffle coats. Also of others who listened to Western music or danced “Western dances” such as rock and roll.

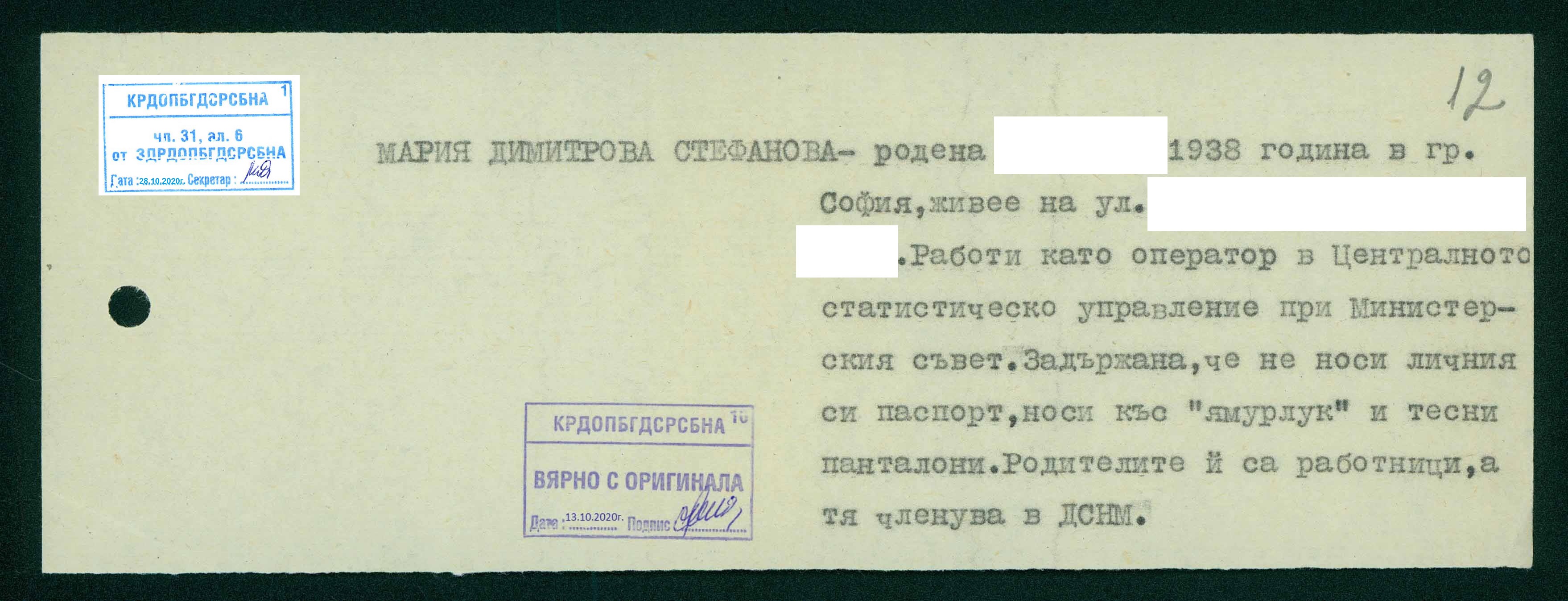

“Arrested without a passport, with a short duffle coat, her parents are former businessmen, opposing to the regime…”

“Arrested as of her duffle coat and indecent hairstyle…”

“Arrested without a passport, with ripped trousers and with her hair in a ponytail, her father is a former officer of the King’s army…”

“Arrested for indecent dancing in the restaurant of TSUM”

The mass arrests took place in very short periods of time – between the 21st of Jan and the 10th of Feb 1958. A big part of the young individuals were arrested and detained in the First Investigative department on st. Moskovska №5. The investigation was conducted with all members of staff of MI and was very brief, lasting only several days despite the large number of arrested individuals. All were pronounced “hooligans” and were sent to the forced labour camp Belene – which is the longest enduring and biggest communist camp on the territory of Bulgaria; and in which thousands of Bulgarian citizens have experienced unbearable terror and violence.

The internment of the young individuals to the forced labour camp Belene took place in groups, first in the beginning of February 1958. At their arrival, they were welcomed by a group of miltsia officers with bats and were beaten violently for 10 kilometres – until they reached the camp’s buildings which were at the heart of the island. They were interned in a separate site, not far from the political prisoners who were sent a year before just after the Hungarian revolution. The young adults were subjected to impossible 14-hour physical labour, beatings, hunger, diseases and brutal punishments.

This operation of State Security took place with the intention of gaining the respect of the young generations and to prevent the ideological influences coming from the West.

In the following years, many young people were accused of dancing to Western music or wearing Western clothing and were too arrested and detained in the cells of st. Moskovska №5. And from these cells, they were moved to the forced labour camp Belene, and after its closure to the forced labour camp in Lovech – where many were violently killed.

Part 4: Memory & architecture

After the repairs of the basements of the building on st. Moskovska №5 in 1972, there was almost no signifiers left of the cells of State Security. As of time, the memory and evidence of the violence had begun to disappear, but the lack of details and the flaws in the obliteration have turn into greater proof of the violence.

After the repairs of the basements of the building on st. Moskovska №5 in 1972, there was almost no signifiers left of the cells of State Security. As of time, the memory and evidence of the violence had begun to disappear, but the lack of details and the flaws in the obliteration have turn into greater proof of the violence.

Buildings are not static at all, quite the contrary, they experience constant and dynamic transformations. Some of them occur far from human’s sight – it takes years for a bubble of air trapped between the paint and the wall to move through the façade of a building.

And since spaces and objects cannot speak for themselves, they need a translator, an interpreter – a person or technology to talk instead them.

That was the role of the rhetors, who use the method of prosopopoeia – a technique of speaking on behalf of objects. The rhetors and scientists gave a voice to the objects, who did not had one by nature. And through the prosopopeia not only it is possible to talk to the unliving, but also as the court pathologists in international tribunes do, to also give voice to silenced cities, countries and communities.

Do buildings remember its past? Do they keep somewhere between the walls, through the dusty ceilings and naked pipes a memory of what they have seen. Do they save the echoes of the words somewhere in their paint or in the different rooms? Do they preserve the touch? Is their memory activated only when they are visited by somebody?

Krasimira Butseva

is a visual artist, researcher and educator based between Sofia, Bulgaria and

London, United Kingdom. She completed a MA (2017) and BA Hons (2016) degrees in

Photography at the University of Portsmouth, UK. She is an Associate Lecturer

at the Media School, London College of Communication, University of the Arts

London. Krasimira is also a recipient of a fellowship at Akademie Schloss Solitude,

Stuttgart/Germany in 2021.

She investigates human rights violations, political violence, traumatic memory, official and unofficial history in the context of Eastern Europe. Her work has been exhibited at the Singer-Zahariev Foundation, Malak Izvor/Bulgaria (2021), Sofia History Museum, Sofia/Bulgaria (2020), Seen Fifteen Gallery (2020), London/UK, District Six Museum, Cape Town/South Africa (2019), Phoenix Art Space, Brighton/UK (2018), Four Corners Gallery London/UK (2017), Pingyao International Photography Festival, Pingyao/China (2016).

Krasimira’s articles “The Politics of Traumatic Memory & Visual Art in Contemporary Bulgaria”, “Vernacular Memorial Museums: Memory, Trauma and Healing in Post-communist Bulgaria” and "Institutional and self-initiated archiving practices. How does APTART manifest on the screen?" are forthcoming in 2022.

She investigates human rights violations, political violence, traumatic memory, official and unofficial history in the context of Eastern Europe. Her work has been exhibited at the Singer-Zahariev Foundation, Malak Izvor/Bulgaria (2021), Sofia History Museum, Sofia/Bulgaria (2020), Seen Fifteen Gallery (2020), London/UK, District Six Museum, Cape Town/South Africa (2019), Phoenix Art Space, Brighton/UK (2018), Four Corners Gallery London/UK (2017), Pingyao International Photography Festival, Pingyao/China (2016).

Krasimira’s articles “The Politics of Traumatic Memory & Visual Art in Contemporary Bulgaria”, “Vernacular Memorial Museums: Memory, Trauma and Healing in Post-communist Bulgaria” and "Institutional and self-initiated archiving practices. How does APTART manifest on the screen?" are forthcoming in 2022.

© History in Between, 2021This project is part of the Cultural Calendar of Sofia, Ministry of Culture and Sofia History Museum.

Connect:

︎ ︎ ︎

„История помежду“ ("Проект за музейни намеси в РИМ, София") е съвместен проект между Фондация „Изкуство – Дела и Документи“ и Регионален исторически музей, София, подкрепен Календар на културните събития на Столична Община.

History in Between (Project for interventions in the Museum, Sofia) is a collaboration between the Art Foundation - Affairs and Documents, and the Regional History Museum of Sofia. It is supported by the Calendar of Cultural Events of Sofia City.